PREVIOUSLY:

“Death No. 4 in Summer Youth Football Conditioning Drills Since 2018 Just in the State of Kansas,” October 17, https://concussioninc.net/?p=15869

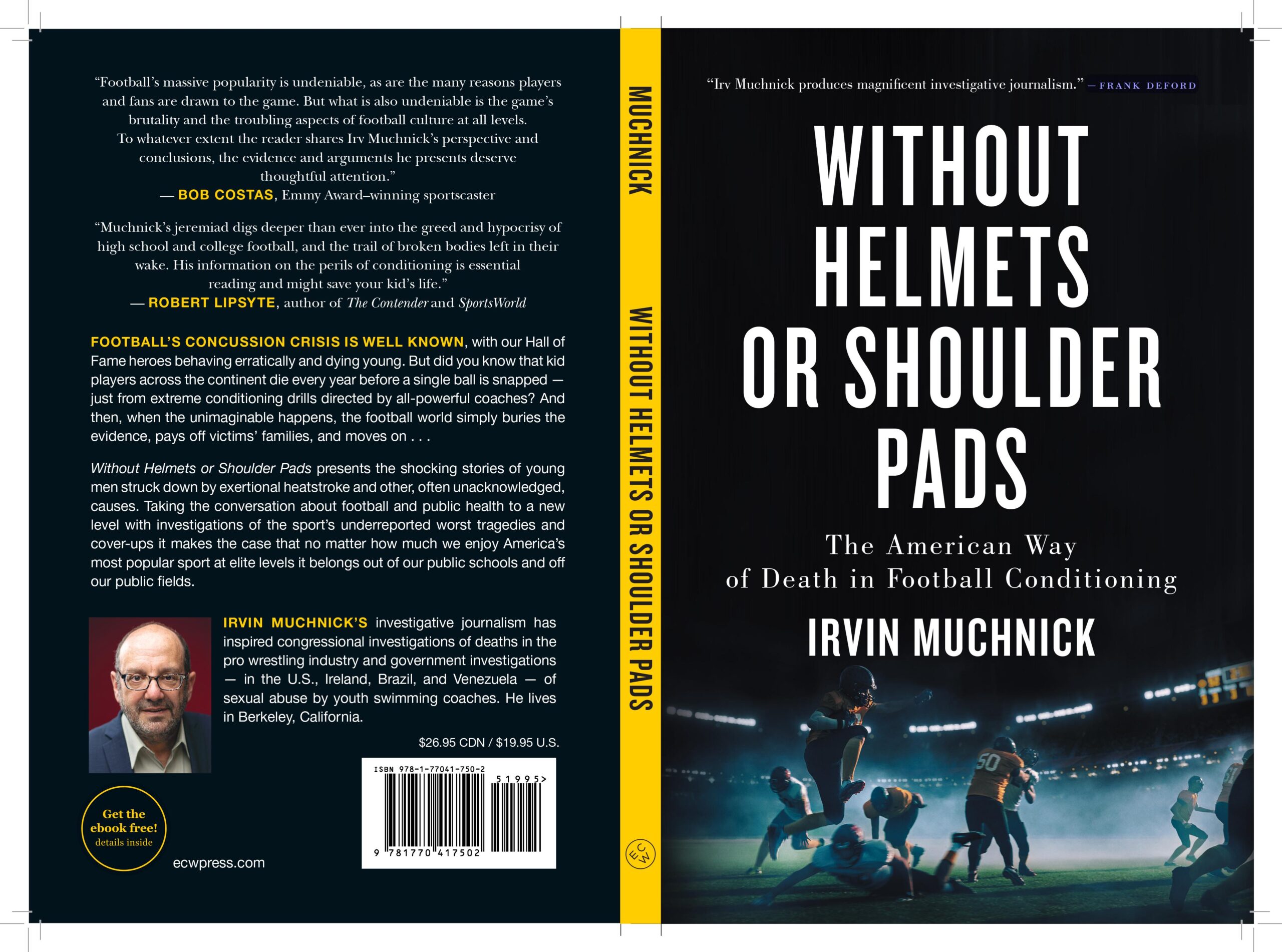

This article is a reprint of Chapter 6, “Bringing the Heat,” of the 2023 book WITHOUT HELMETS OR SHOULDER PADS: The American Way of Death in Football Conditioning.

by Irvin Muchnick

Mothers of soldiers the world over who get that knock on the door with the most horrible news, unimaginable news, are familiar with the process. For the mom of Braeden Bradforth, a 19-year-old offensive tackle, realization came in stages. No one from Garden City Community College called. There were only cryptic patches of reports from other loved ones who struggled to form the words. Even when they finally found a way to tell her that her Braeden had fallen, for good, in the remote southwest corner of Kansas, more than halfway across the continent, on the far edge of the next time zone, Joanne Atkins-Ingram couldn’t quite process it.

In southern New Jersey, it was already well past midnight, early Thursday morning, August 2, 2018. A state employee on the brink of retirement, Joanne had just finished her volunteer shift at a homeless shelter in Freehold, where she helped out regularly. This was her first night back there in a while, since recovering from surgery. And the last days had been such a whirlwind! It was barely a week since Braeden — not yet sure just what he was supposed to be doing with his life after graduating from Neptune High School on the Jersey Shore — first learned that Garden City Community College, of the Kansas Jayhawk Community College Conference, was inviting him to play football for them. So it came to pass that a mere four days later, Joanne was driving Braeden up the Garden State Parkway to Newark Liberty International Airport, and seeing him off on a 6 a.m. American Airlines flight to Garden City by way of Dallas. This was Braeden’s second time on an airplane. He hit the campus in mid-afternoon, submitted his paperwork to various offices before the end of the deadline day, and moved into the college’s West Residence Hall.

In phone calls, Braeden told his mother he was settling into his dorm and making friends. He bonded and played video games with C.J. Anthony, a wide receiver from Atlanta. Anthony even somewhat resembled his new buddy, all the way down to the dreadlocks.

On Wednesday, Joanne talked with Braeden twice, once in late morning and again in early evening. Braeden reminded her to send off the care package she’d promised him — and not to skimp on one of his favorites, Golden Oreo cookies. In the second call he said he was about to head off to the second practice of the football team’s first day. He expressed a little concern that he might not be in the best of shape for what lay ahead. The day before, Braeden had said some of the same things in a conversation with his high school coach, Tarig Holman.

Before hanging up, Braeden said, “I love you.”

“I love you, too, Tubby,” Joanne said, using the family’s nickname for him. “We’re so proud of you.”

Near 1 a.m., after Joanne closed down her work at the homeless shelter and was about to make the half-hour drive back from Freehold to Neptune City, Braeden’s older brother, Bryce, called. Haltingly, he said it was about Tubby. He said police were at their house. Otherwise, Bryce was incoherent, making no sense, and it sounded like he was in tears. Joanne was confused; it didn’t register, not consciously anyway, that Bryce was trying to communicate that something terrible had happened. She told Bryce that if he had something to say, he should come right out and say it. But Bryce couldn’t.

Joanne called her husband, Robert “Bo” Ingram Jr., Braeden and Bryce’s stepfather, a truck driver who was completing a delivery in Philadelphia. She asked Bo what was going on. After an awkward silence, Bo said he’d find out and call her back. He did so a few minutes later.

“I don’t even know how to say this,” Bo said to Joanne. “Tubby is . . . gone.”

“Gone where?” Joanne replied. Braeden had just arrived in Kansas. A gentle giant of considerable charm, with a unique relationship to his surroundings, he was notorious for his navigational eccentricity. But, after all, how lost could someone get on his third night on a junior college campus?

Then it hit her. By gone, Bo didn’t mean Braeden was missing or lost. Gone meant dead. Somehow, in the stewardship of his new football coaches, the child Joanne had whisked off to Kansas for the adventure of his life hadn’t survived 72 hours. She didn’t yet know exactly what had happened, and as the evidence unfolded, it would become clear that she probably never would. But in that instant it finally dawned on her that Bryce’s earlier shambolic demeanor was for the most tragic reason: his brother — her second son — had just perished, suddenly.

That’s when Joanne Atkins-Ingram screamed, and everything went black.

***

At six-foot-four and ranging up to 315 pounds, Braeden Bradforth called to mind Michael Oher, the hulking Tennessean who won a Super Bowl ring playing on the offensive line of the Baltimore Ravens; Oher’s extraordinary rise from foster care and homelessness was featured in the book and movie The Blind Side. Unlike Oher, though, Braeden had enjoyed a stable two-parent home life. He wasn’t a good student, but he was a good soul. He loved children and was a soothing presence for not only his own dog, Duke, a pit bull, but also even the most snappy of his friends’ pets. His bedroom on the second floor of the house in Neptune City was filled with stuffed animals. His dreads, flowing across the temples of his eyeglasses, and his goatee contributed to an aura of a bohemian, maybe some kind of frumpy intellectual, in addition to a happy-go-lucky jock.

Braeden’s girth made him a natural to try football. And once he learned how to harness his size to a semblance of blocking technique, and not to hold back from hitting hard, he found he excelled at it. With her busy work schedule, and with Bo often unavailable on trucking assignments, Joanne managed to get her Tubby around to all his American Youth Football League practices and games by leaning on her network of local Facebook friends. Borrowing a page from Hillary Clinton, Joanne called them her “village.”

At Neptune High, the coach under whom Braeden played, Tarig Holman, owned a quirky footnote in football history: as a cornerback for the University of Iowa in a 1998 game, Holman on successive possessions intercepted passes thrown by the University of Michigan’s quarterback, the soon-to-be-legendary Tom Brady. In Braeden’s senior year, Coach Holman helped him put together a highlight reel of his top plays. In addition to sending off hard copies of this video to recruiters for perceived possible landing spots, Braeden posted it on hudl.com, a website where football hopefuls seek to catch the attention of college athletic scholarship gatekeepers.

Unfortunately, Braeden got no bites. He thought his football journey might be ending with the All-Shore Gridiron Classic, a regional all-star game staged on July 12 at the high school field in neighboring Brick Township. From there, perhaps he’d enroll at an area junior college, and either play football or not. There was a regional junior college consortium team called the New Jersey Warriors.

In the spring of 2018, an assistant football coach from Garden City, Steve Shimko, had passed through South Jersey. At a track and field team practice, Shimko caught sight of Braeden throwing shot put and discus, and was impressed by his form, athleticism, and power. Over the summer, Shimko left Kansas to take a job as the assistant quarterbacks coach of the NFL’s Seattle Seahawks. But he must have left a favorable report with his old colleagues, since on Thursday, July 26, Braeden got an email response from another assistant coach in Garden City. Would Braeden like to matriculate and play football there?

When Braeden shared the news with Joanne, he was over the moon. In the email from the assistant coach, Garden City wasn’t offering a scholarship — but then again, junior colleges had open enrollment and only nominal tuition and fees.

One of the first orders of business for son and mother was locating Garden City, Kansas, on a map. For lifelong east coasters, this town with a population of less than 30,000 took the middle of nowhere to new levels. Garden City was located nearly 400 miles west of Kansas City, Missouri, more than 200 north of Amarillo, Texas, more than 400 northeast of Santa Fe, New Mexico. According to the Internet, Garden City had a good zoo and a claim to literary infamy: it and nearby Holcomb were settings of Truman Capote’s classic nonfiction murder novel In Cold Blood. There were well-paying jobs in the meat-packing industry in Garden City, and it was becoming a place of surprising racial diversity. The school had a heavily enrolled English as a Second Language program.

After a Garden City admissions representative talked with one of Braeden’s high school teachers, he and Joanne were off and running in a flurry of paperwork, preparation, and packing. They called the Neptune High registrar’s office, and a transcript was dispatched. Braeden’s local doctor, Kristen Atienza, gave him a rush physical exam and certified on the Preparticipation Physical Evaluation form that he was “cleared without restrictions.” Dr. Atienza did add a note that his body mass index, 36.5, marked him as clinically obese and called for diet and exercise measures.

Late Sunday night, Joanne and Braeden made the obligatory shop at Walmart for last-minute items. Through the excitement of those days, Joanne also shared this family development with her Facebook “village.” Friends weighed in both with tips and, materially, with fundraising for Braeden’s plane ticket. Joanne acknowledged maternal tremors over sending her son from her nest so abruptly. She wondered if she was making the right decision.

“Don’t worry, Joanne,” one villager messaged back. “He’s in good hands.”

***

That last remark might not have been made if this circle of New Jerseyans knew that Garden City Community College was in the most turbulent period of its century-long history. Braeden Bradforth’s football-focused landing spot was an institution out of control in every way.

Like many junior colleges, GCCC was an underappreciated local jewel, full of dedicated teachers on modest salaries who considered their jobs a calling, and bustling with bootstrapping young adults from underserved populations — not all of whom harbored profound academic ambition, but almost all of whom regarded their school as a gateway to better opportunities. But GCCC was going through a chaotic patch under its current president, Herman Swender. In 2017, the Higher Education Commission, the Chicago-based accreditation overseer, put the school on probation in the wake of a series of irregularities, all of them flowing from Swender’s toxic leadership. His antics included toting an open-carry gun, threatening faculty and staff for speaking with journalists, searching their emails and cell phones, requiring prayers at the start of meetings, and in general administering a workplace rife with division and dysfunction. Three months before Braeden arrived on campus, the trustees commissioned an outside investigation of the Swender regime. Six days

after Braeden died, the president’s resignation would become official.

The school’s athletic department, specifically, reeled with scandal. The director of the cheerleading squad, Brice Knapp, resigned amidst allegations of sexual harassment and abuse. One of the athletic directors passing through the revolving door, John Green, was found to have moved a female volleyball player into his house. There were outstanding complaints relating to Title IX, the federal law barring sex discrimination in educational programs. There were various allegations that could have led to athletic conference sanctions. There was a possible U.S. Department of Education investigation of financial aid violations.

Jeff Sims was the head football coach and also held the title of assistant athletic director. Sims was a nomadic but continuously employed figure on the college sports system’s lower rungs. In 2016, he’d led the GCCC Broncbusters to the national junior college championship. GCCC marked at least the 11th stop in his football coaching career, including two separate stints as an assistant at Indiana University.

Sims also was a leading voice in the public debate over the structure of Kansas junior college football. Starting in 2016, a documentary series on Netflix called Last Chance U explored life in the sport’s bottom-feeder programs. Like much of reality television, the series was simultaneously exploitive and oddly informative. The main theme coming across was that football-obsessed young men throughout the country, from hardscrabble backgrounds, were going to extraordinary lengths to nurture dreams of participating in the glory and riches of football’s elite levels.

Housing top amateurs from ages 18 to 22 or so, the NCAA has around 125 Division I football programs alone, wherein an astonishing percentage of the more than 5,000 student-athletes have the goal — much closer to a pipe dream for the supermajority of them — of being drafted into the NFL. Below these are the NCAA’s lower divisions. And below them are junior colleges, or JUCOs, under the umbrella of the National Junior College Athletic Association (NJCAA), where student-athlete goals differ little from those of the talent in multimillion-dollar college football factories. The only real distinction is that JUCO teams are largely comprised of the rejects from the more prestigious programs; these include players who simply couldn’t get admitted to a four-year university because of poor grades or other factors. Combating food insecurity and lack of affordable housing options, some deploy desperate lifestyle strategies.

Even so, the grapevine promotes just enough anecdotes of the careers of NFL stars who used the JUCO path to word-of-mouth Hail Mary sustenance and success. For example, Tyreek Hill was a standout wide receiver at GCCC who wrangled a transfer to Oklahoma State University, and from there got noticed by NFL scouts. The connection of quarterback Patrick Mahomes throwing passes to the speedy, shifty Hill was a large part of the Kansas City Chiefs’ Super Bowl–winning formula in 2019–20.

For Braeden Bradforth, enrolling at Garden City Community College meant punching his own ticket at Last Chance U.

Founded in 1923, the Kansas Jayhawk Community College Conference (KJCCC) was a long-time hotbed of JUCO football, in all its often charming small-time passion and fanaticism. In the 50-plus years since 1962, the conference had taken a step to contain those forces and keep its brands localized, by implementing a rule that no school could carry more than 20 football players from out of state. A similar cap regulated the other so-called high-revenue sport of men’s basketball (where roster sizes are much smaller). But in 2015 the caps got lifted. Additionally, football team rosters on the whole were expanded from 63 to 85.

(On the issue of the KJCCC out-of-state cap, but also on several other key aspects of the Braeden Bradforth story, I’m indebted to the excellent in-depth coverage of Sam Zeff of KCUR radio in Kansas City, a Public Broadcasting System affiliate.)

One program quick to exploit the lifting of the cap was Independence Community College in Montgomery County — east of Garden City but likewise near the state’s southern border with Oklahoma. On Last Chance U in 2016, the Independence football coach, Jason Brown, said, “We’ve got to turn over rocks and find kids at all costs.” The next year, Brown’s squad carried 69 players from outside the state. Meanwhile, in basketball, only 121 of the 540 men’s players throughout the conference were Kansans (five of them hailed from the African nation of Mozambique).

Brown’s counterpart at GCCC, Sims, was a fellow outspoken opponent of the cap. Sims framed it as rooted in racial discrimination, limiting the opportunities of young African-American men everywhere to find a foothold for their football marketability in the small towns of the Sunflower State. Despite the vocal opposition of Brown, Sims, and others, the KJCCC reinstated a modified cap a year after Braeden Bradforth’s death. Today, no more than 55 members of the 85-man football rosters can be from out of state. This still represents a lot of the equivalent of football migrant labor: disproportionately student-athletes of color seeding the gridiron populations of largely white, rural JUCOs.

***

The misgivings Braeden expressed to his high school coach and to his mother about his preparedness for the start of GCCC practice proved prescient. Over the summer, other members of the team had received a package of schedules and instructions from Coach Sims and his staff, laying out their expectations for early conditioning drills and other responsibilities; the document was entitled “Garden City Football, Opportunity USA, 2018.” Braeden, of course, hadn’t seen it. Also, he was being dropped right into intensive conditioning drills with no accounting for the transition from the Jersey Shore, at sea level, to the half-mile altitude of the Kansas high plains. On Wednesday, August 1, the temperature was 84 degrees with high humidity.

Braeden Bradforth, in less than tip-top shape, was a disaster waiting to happen.

At least two players, Johnny Jean and Kahari Foy-Walton, would tell the media that the ten coaches, one trainer, and eight student helpers who were present on August 1 either explicitly or implicitly denied the squad access to basic hydration. Later, GCCC’s investigation would dispute this, stating that 60 gallons of water were on site and the student helpers had individual bottles in their carriers to hand out to anyone requesting them.

The more subtle conclusion is cultural: Coach Sims’s words and gestures likely discouraged water breaks. This was all in the tradition of football’s vague but seemingly ineradicable code of prioritizing “toughness,” an indispensable component of which was never betraying “weakness.”

One player, Kirby Grigsby, said that while water was there, he and his teammates had the perception they’d be punished for partaking it. “If you got water, you were considered done. [That meant] it was basically over and you had to do your conditioning all over again the next morning.” Grigsby further explained that Sims and his assistant coaches “said that water during workouts does nothing for you. It’s how you hydrate ‘before’ and ‘after.’”

The evening drills involved 36 sets of 50-yard sprints, with breaks of no more than 30 seconds between each one. As they progressed, a student assistant, Donte Morris, noticed that Braeden was wheezing. A fellow lineman, Olajuwon Lewis, running alongside, observed his dry mouth and his lips turning white.

According to some of the players, Sims taunted Braeden as he labored to keep up. His new friend, C.J. Anthony, may have been the only athlete on the field who actually completed his sprints at the required times (six seconds per 50 yards for skill position players, eight seconds for the others). Anthony noticed that the coach, who’d lent Braeden a pair of shoes to use at practice, yelled that he wanted his shoes back. Others corroborated this and added that Sims cursed and screamed that Braeden was “soft.” At one point, Braeden fell to his knees and grabbed his chest; Sims ordered him to get up and continue.

Anthony: “I remember the pain on his face. He couldn’t breathe. The coaches were telling him he was just being dramatic, to stand up. . . . I could tell he was out of whack. By the tenth one or so he wanted to stop and the coaches started chewing him up. Coach Sims was saying all kinds of stuff you never say in front of other players: ‘Your dad says you work hard, but you don’t.’ Stuff no one wants to hear. You could see the pain in his eyes, like he wanted to cry, but instead of doing that he just sucked it up and kept going.”

Anthony said he, himself, felt like he was going to die, “and I was in the best shape of anyone there.”

The drills ended around 9:15 p.m. Braeden was the last in line leaving Broncbuster Stadium. An assistant who coached the defensive safeties, Caleb Young, saw him sitting in the stands with his head in his hands, and prodded him to move along. The team trekked the short distance toward the Dennis Perryman Athletic Complex for their first indoor gathering. Sims called it the “Winners Meeting.”

After a few yards, Braeden stumbled off in another direction, toward the dormitory complex on the western edge of campus. It’s unclear whether he was making a conscious decision to veer off. There was a brief exchange of words with Young, the upshot of which could have been either that the coaches were dismissing Braeden from the team or that he was resigning himself. In an email to school administrators nearly a month later, Young said he asked Braeden if he was quitting, and instead of responding with words, “he shook his head in what looked to me disappointment and continued to walk away.”

Given Braeden’s physical exhaustion to the point of critical illness, any conversation between the teenager and the coach, using either words or body language, couldn’t have been very sophisticated. Braeden’s prospective status on the team aside, he was in acute distress, yet was being allowed by the coaching and training staff simply to wander off. Indeed, in the wake of the grueling session, the trainer TJ Horton and his student assistants weren’t bothering to check the welfare of anyone. They were busy breaking down equipment and putting it back into storage.

While the group convened at the athletic complex, it’s speculated that Braeden tried to enter the West Hall dorm by the wrong passage, a locked door at the end of a narrow alley where the heavy air was even more choked. All that’s known for sure is that he must have sat down in that alley and rested his head against the brick side of the building.

Back at the Winners Meeting, Young told Ben Bradley, the offensive line coach, along with head coach Sims, that Braeden had quit the team. Addressing the players, Sims sneered over Braeden’s aborted Broncbusters career. “This kid didn’t even finish the running today,” the coach said. “He was slacking. He didn’t even have a pair of shoes to lift in, but I gave him a pair of shoes.” Sims said he felt disrespected and was directing Bradley to tell Braeden to “give me my shoes back.”

The meeting broke up around 9:45. Routinely, the players showered back at home. A group of them walked toward the residential complex. Several, probably about five of them, spotted Braeden in the alley. The exact number of teammates gathered around is hard to say, since this was the first practice day and not everyone knew everyone else. Braeden likely had been slumped or lying there between 20 and 30 minutes.

Kirby Grigsby was one of them. Braeden “was in bad shape,” Grigsby remembered. “He was trying to breathe. He was making like a humming noise as he was trying to breathe and I could tell he was not able to breathe like he wanted to. His eyes were closed, his tongue was sticking out.”

In clinical terms, Braeden was “obtunded” — he had a dulled level of alertness and consciousness.

Someone hurried back to the athletic center, returning with Caleb Young, the assistant coach. Grigsby and others poured water into Braeden’s mouth. Someone on the team staff — Young or another assistant — hosed down his body, evidently using a hookup at the side of the building, language in the subsequent Emergency Medical Services report would suggest. Young was reassuring the kids that Braeden would be OK. In that email to administrators a few weeks later, Young described “visible distress at this time however still breathing and making a stressful moan.”

Young didn’t call 911. Instead, he called head coach Sims for guidance. Sims told him to call Horton, the trainer. At 9:53, Young hailed Horton at home. Horton got there at 9:59. He didn’t have 911 summoned, either, until 10:02.

EMS Unit 97, with paramedics Christine Macias and James Good, arrived with a screech at 10:10. In their report, they said “the coaches made all players go back to rooms so any witness(es) . . . were not present at this time.” Braeden “was moaning and was wet. There was also a lot of water on sidewalk around him.”

According to the report, “Coaches were only able to provide minimal patient history. Coach states patient had asthma and used an inhaler. Coach also stated he had seasonal allergies.” Though Braeden’s medical history included passing reference to asthma, interviews for a later GCCC investigation of the incident had no references whatsoever to asthma or allergies.

The EMS crew found Braeden unresponsive when they rubbed his chest. They measured his blood glucose level. He choked and started vomiting; Young would describe the upchuck as resembling “dirty motor oil.” When the vomiting stopped, Braeden was loaded onto a soft stretcher and into the back of the ambulance. At 10:24, the medics designated a “code red” emergency.

At 10:33, the unit pulled up to the emergency entrance of St. Catherine Hospital. On the Glasgow Coma Scale, Braeden was deemed a 4 (a patient is considered comatose at anything under 7). Soon, his heart stopped. At 11:06, he was pronounced dead. A hospital pastor called the family in New Jersey. That’s how older brother Bryce got word.

By then, head coach Jeff Sims was at the hospital. His message to the news media was that an emergency room doctor had told him of a test performed on Braeden indicating “a blood-clotting disorder.” Sims said a blood clot likely broke free, traveled to his heart, and caused a heart attack.

There’s absolutely nothing in the records, contemporaneous or retrospective, coming anywhere close to supporting such a hypothesis. The medical records indicate that Braeden was administered something called a D-dimer test, which looks for the presence of a protein fragment known as a fibrin degradation. The D-dimer test had zero weight in the assessment of the cause of death. Notably, the preliminary report of the coroner’s office — an intake document as the first steps of the autopsy were contemplated — had no reference to a blood clot. And everything intuitive — all that was observed and done on the spot, including the immersion of Braeden in water, by amateurs and professionals alike observing his critical state — pointed only to unanimous speculation, with near-certainty, that the cause of Braeden’s collapse was exertional heatstroke.

Still, Sims stuck to his guns throughout that key initial news cycle, most effectively in an interview with Sports Illustrated online. SI’s article and other short items on the wire services framed the narrative of yet another sudden death, of a football player of no distinction, in a remote place.

Or as Sims put it: “Something that could have happened, anytime or anywhere . . . an act of God . . . ”

***

The Finney County medical examiner’s autopsy report took nearly four months for finalization and public release. The one-sentence summary of the 11-page report by the forensic pathologist, Dr. Eva J. Vachal, said it all: “Considering the facts surrounding the case, the cause of death is judged to be exertional heat stroke.” In the commentary, Vachal went out of her way to debunk the theory of a blood clot by writing that there was “no evidence of pulmonary thromboembolism.”

By the time the report got filed in state court, on November 29, Jeff Sims’s football team was in Pittsburg, Kansas, preparing to play the national JUCO football championship game against East Mississippi. I caught up with Sims that day on email.

The coach wrote back to me, in substantial part: “While newspaper headlines may lead some to believe that Braedens Death [sic] had a connection with football or practice, it did not. It was unfortunate timing but truly is there ever a time that we expect the passing of a young man. Braeden passed away the evening after practice and we have been assured it was something that was out of our control. We all miss Braeden, GOD has his timing.”

The GCCC–East Mississippi championship game was broadcast nationally on a tiered CBS Sports cable network. The Broncbusters lost, 10–9. The broadcast included no mention of the Braeden Bradforth death in August or the breaking news surrounding it.

In response to my queries, a spokesperson for CBS Sports had disclaimed any responsibility for the content of the upcoming broadcast. CBS said it was merely the carrier of the game; the producer was an independent company called Kitay Productions, which didn’t return my messages. On December 1, I heard back from the company’s owner, Joel Kitay. He explained that the delay had been caused by “being so busy getting ready to get on the air.”

As to Braeden Bradforth, Kitay said: “Our announcers were aware of this, and it was discussed in detail when we had a phone call with the head coach prior to the game. It was up to the announcers to bring it up on air if the topic came up naturally in the flow of the game, which it did not.”

***

By the time of the JUCO championship game, Sims had already accepted a promotion in the college football world. He was on the move again. Two days later, he became the head coach at Missouri Southern State University in Joplin, with a three-year contract — his 12th career stop. GCCC didn’t clarify whether Sims’s departure was fallout from the Bradforth death. Nor did MSSU clarify whether, in interviewing Sims for the job, he was asked to account for Braeden’s death, or if the incident was even communicated to or factored into the decision of those who approved the hire. The Joplin Globe later would confirm that MSSU, unsurprisingly, knew all about the GCCC fatality on the prospective new coach’s watch.

Sims coached only one season in Joplin before being dismissed, as the Bradforth death litigation unfolded in Kansas and as politicians and media commentators amplified the demand for answers there. Under his tutelage, MSSU won only two games and lost nine, so there was that. Even though dismissing Sims had fiscal implications, the university refused even to say whether or not he was being sacked, in the legal jargon, “for cause.” (Sims was fired in December 2020, two years after he was hired. But the 2020 MSSU football season got wiped out by the pandemic.)

In 2022, KCUR radio’s Sam Zeff reported that the NCAA’s Division II Committee on Infractions had issued a 25-page report delineating violations at the MSSU program, “where compliance was an afterthought, if not entirely dismissed and disregarded. . . . Apart from directly committing and not addressing known violations, the head coach created and maintained an adversarial environment between his program, athletics leadership, and compliance professionals.” To cite one example, an MSSU booster was enlisted to pay the back tuition bill for one of Sims’s former players at GCCC so that he could transfer to MSSU. The report led to sanctioning the Missouri university with a reduction in athletic scholarships, a $5,000 fine, and three years’ probation.

In the wake of the Bradforth death, GCCC undertook what it called an internal review. A later and more expansive investigation would expose the “review” as a sham, even worse than the cursory initial investigation by Cal after Ted Agu’s death. GCCC’s was driven by such testimony as Caleb Young’s email memorializing the events of the fatal conditioning session and its aftermath. The report was haphazardly assembled by the interim athletic director, Colin Lamb; the campus police chief, Rodney Dozier; and a student services official named Tammy Tabor. The reviewers conducted no interviews and flatly concluded that nothing untoward had happened in the actions of college personnel.

Braeden’s mother, Joanne Atkins-Ingram, and her friend and lawyer, Jill Greene, had no success in eliciting details or background from the GCCC administration. They were given, for example, conflicting information about the existence of campus surveillance video, which might have shed light on Braeden’s wandering back to West Hall and the last hour of his life.

In mid-August 2018, while making arrangements to have Braeden’s belongings shipped back, Joanne spoke with Christine Dillingham, the office manager of residential life, who told her that wide-angle video existed of the stricken Braeden. However, college lawyer Randall Grisell, in response to attorney Greene’s “spoliation” notice warning not to destroy possible evidence, claimed there was “no relevant reason” to produce any videos that might exist. Ultimately, the women were given the explanation that there was no surviving video, since surveillance camera footage, maintained by the campus police, got routinely overwritten every two weeks, an economy of limited computer server capacity. Why the college believed that video providing details of a death on campus was an immediate candidate for erasure will forever remain a mystery.

In late January 2019, Atkins-Ingram and Greene paid out of their own pockets to fly to Garden City. They visited the spot where Braeden collapsed, talked with numerous teammates and local witnesses, and ignited media coverage. Some of the stories moving forward would land in the Gannett chain’s Asbury Park, New Jersey, newspaper, the Press, but there were also critical news and opinion articles published and broadcast closer to the scene of the crime. In November, a scorching editorial writer for the Kansas City Star had written, “If coach Jeff Sims had any awareness, he would quit coaching today.” In March, opining on Missouri Southern State University’s hire of Sims, the Joplin Globe editorial page would call for a full accounting by both the local institution and GCCC.

Just before Joanne left for Kansas, her New Jersey state senator, Van Gopal, wrote to the Kansas attorney general, Derek Schmidt, demanding an independent investigation of the death “and the professional practices of the Garden City Community College Athletics Department. This matter needs the force, authority, and expertise that only the Kansas Attorney General’s Office can provide.” Schmidt refused, claiming he lacked such authority.

In March, U.S. congressman Chris Smith, of New Jersey’s Fourth District, got involved with a public letter to Ryan Ruda, GCCC’s new president, advocating an independent investigation. Smith called Ruda’s response to his letter “legalistic,” “rude,” and “condescending.” In support of the campaign for an investigation, the Republican Smith later would pull together a bipartisan coalition of all 12 of New Jersey’s House of Representatives members. They included Frank Pallone, a Democrat who chaired the powerful House Energy and Commerce Committee.

On the Jersey Shore in April, more than 100 friends and neighbors packed Asbury Park’s Friendship Baptist Church for a town hall meeting to support Joanne’s campaign for answers. Congressman Smith told the gathering he’d be introducing legislation for the creation of a commission to investigate the deaths of college football players. Smith also announced that GCCC president Ruda had agreed to meet with Joanne later that month. But the negotiations for the meeting would collapse over GCCC’s preconditions; specifically, the college did not agree to share with her its “internal review.”

The next month, the college released a page-and-a-half summary of the review. This claimed that the 84-degree temperature at the August 1 practice was seven degrees below normal for that date; that water, Gatorade, and ice towels were in abundance; and that no one saw Braeden falter during the drills.

In response to an overture from Congressman Smith, Kansas governor Laura Kelly weighed in with a letter — not to him but to Joanne. Kelly said she’d heard that Braeden “was a promising young man” and noted that she was herself a mother, “and I can only imagine the anguish you must feel.” The governor, however, stressed that she had no role in the administration of Kansas community colleges, which are governed by elected boards of trustees.

In late spring, the GCCC trustees authorized an investigation funded at $100,000. Randy J. Aliment, of the college’s outside counsel, the Lewis Brisbois law firm, and Rod Walters, a sports medicine consultant, were selected as co-authors.

Preparing to litigate, Atkins-Ingram and Greene retained a Kansas co-counsel, Chris Dove. In the end, the prospect of a wrongful death lawsuit was hamstrung by the Kansas legal doctrine of “qualified immunity” for state public agencies, which capped recoveries at $500,000. Eventually the parties settled for that maximum amount.

GCCC’s investigation of Braeden’s death, by Aliment and Walters, was published in October 2019. The 48-page report highlighted “a striking lack of leadership” by former college president Swender, former athletic director John Green, former head football coach Jeff Sims, and head athletic trainer TJ Horton. The report proceeded to lay out how their failures manifested in no oversight of the preparation for and execution of the fatal conditioning test, and in significant delays in response after Braeden was stricken.

***

Exertional heatstroke (EHS) is the leading killer of kids during football conditioning. The most foolproof way to save the life of a victim? Immerse him in an ice bath, immediately. This is 100 percent effective in preventing death.

Supposedly, consciousness-raising and good modeling start from the top, where bad things happen to millionaire celebrity athletes. On August 1, 2001, Korey Stringer, a 350-pound offensive tackle for the Minnesota Vikings, died during training camp in Mankato, Minnesota. On July 30, the first day of practice, he’d left early due to exhaustion. The next day, Stringer willed himself to participate in drills again, and during the morning session of two-a-days, vomited three times. Afterward, in the air conditioned locker room, he became weak and dizzy. He was rushed to the hospital, lapsed into unconsciousness, and died in the early morning hours. This happened to be exactly two days before the death, chronicled in the first chapter, of the asthmatic Rashidi Wheeler at Northwestern. It was also 17 years to the day before Braeden Bradforth succumbed to the heat in Garden City.

With funds from her ensuing lawsuit settlement with the Vikings, Stringer’s widow, Kelci, spearheaded several EHS initiatives to honor her husband’s legacy. These efforts culminated in 2010 with the establishment of the Korey Stringer Institute at the University of Connecticut, which is dedicated to preventing sudden death in sports, especially from EHS.

Unfortunately, when I contacted multiple officials from the institute for this book, none came forth with any data on EHS incidents or deaths. In the last chapter, I’ll have more to say on how football safety studies, undertaken by think tanks and academic entities with ties to the industry, fall miserably short in disseminating pointed and useful public health information, much less in advocating effectively from such data.

One thing that can be said about EHS — in contrast with exertional sickling — is that it’s distributed with racial neutrality; the main variables are the intensity of the heat, the size of the athlete, and the extremities of philosophy and safety inattentiveness of the supervising coaches and training and medical staff. One highly publicized victim of recent years was neither Black nor large. In 2017, 16-year-old Zachary Martin-Polsenberg collapsed during sprints at a football practice at Riverdale High School in Fort Myers, Florida; he was taken off life support 11 days later. His mother, Laurie Giordano, set up the Zach Martin Foundation in his memory. In 2020, the state legislature passed and Governor Ron DeSantis signed the Zachary Martin Act, which mandates defibrillators and immersion tubs at game and practice venues. According to a 2019 report by the Florida Office of Program Policy Analysis and Government Accountability, there were 18 EHS cases at high schools in the state the previous year — and this survey didn’t even cover football summer practices.

The 2010s were an especially taxing decade for American youth football EHS fatalities; seven teenagers died from this cause in Louisiana alone from 2012 through 2019. Whether this is an accelerating trend, compounded by rising temperatures from the global climate crisis, or perhaps merely a function of better reporting, could come into focus once pandemic disruptions of sports programs are fully in the rearview mirror.

In 2018, media coverage of the EHS death of the University of Maryland’s Jordan McNair lapped many times that of Braeden Bradforth’s a mere 49 days later. This was understandable, since Maryland is an NCAA Division I school. Additionally, McNair’s narrative combined EHS boilerplate with the “toxic culture” overtones at Ted Agu’s Cal. And in a rare and seemingly anomalous turn of events, several figures actually paid for their shortcomings with their jobs.

On May 29, McNair, a 325-pound offensive tackle, collapsed during practice. At the hospital, his body temperature was recorded as 106 degrees, and he was airlifted to a trauma center, where he got an emergency liver transplant. McNair died on June 13.

To his credit, the president of the university, Wallace Loh, issued an extraordinary statement that the institution “accepts legal and moral responsibility in the death of football player Jordan McNair.” Nearly two and a half years later, the university paid a $3.5 million settlement to the McNair family.

Meanwhile, the larger accountability engine churned, by fits and starts. An ESPN report targeted the environment created by the football strength and conditioning assistant, Rick Court, where players were belittled and humiliated. It all sounded a lot like Damon Harrington at Cal. As one witness put it to ESPN: “I have heard players and myself called ‘pussies’ for being unable to complete workouts and the constant foul language has become accustomed to our culture. It has been incorporated into how we spoke to our teammates and coaches, but it isn’t seen as a negative because we are so numb to it now.”

In the familiar pattern, the Maryland regents commissioned a study of the football program (it was prepared by sports medicine consultant Rod Waters, who soon would co-author the same exercise at Garden City). When the report was issued in September, the university cut loose conditioning coach Court, but the head coach, D.J. Durkin, remained on the job. Local and national outrage didn’t abate. On October 30, 2018, President Loh announced his own upcoming retirement the next year. (For technical reasons, his departure wound up not taking effect until the middle of 2020.)

The very next day, Maryland fired Durkin. In 2020, he latched on as an assistant to Lane Kiffin at Mississippi. In 2022, Durkin moved to Texas A&M as the defensive coordinator under Jimbo Fisher. With the passage of more time, Durkin’s complete rehabilitation, in the form of another head coaching post, is considered not out of the question.

***

Almost exactly three years after Braeden Bradforth — on August 4, 2021 — Kansas junior college football recorded another exertional heatstroke fatality. It was strikingly similar, almost identical. Tirrell Williams dropped dead at Fort Scott Community College, 80 miles south of Kansas City. Like Bradforth, Williams weighed more than 300 pounds. Like Bradforth, Williams was 19 and African-American. After his transfer from a local emergency clinic, he lay in a coma for two weeks at University of Kansas Hospital in Kansas City, before expiring from the official listed causes of oxygen deprivation, septic shock, and muscle tissue damage.

(Muscle tissue breakdown suggests the possibility of rhabdomyolysis from exertional sickling, but I wasn’t able to determine whether Williams was a sickle cell trait carrier or if he was ever screened.)

The college had told Williams’s mother in Louisiana, Natasha Washington, that his hospitalization was precautionary. “I was never told that he was non-responsive,” she said. Only when a hospital nurse told Washington that her son’s condition was dire did she dig deep to buy a plane ticket to be at his bedside.

KCUR’s Zeff reported that the incident stemmed from the Fort Scott head coach, Carson Hunter, discovering a candy wrapper on the field and proceeding to punish the whole team with a previously unannounced set of back-and-forth sprints. Coaches call these “gassers.” Hunter added “up-downs,” in which the athletes were directed to drop to the ground on their stomachs and pop right back up.

Tanner Forrest, the trainer, told Zeff that Williams collapsed, falling face-forward to the dirt, on “gasser number eight or nine.” Coach Hunter stopped the workout briefly as two assistant coaches knelt to check on him. The drill resumed while Williams lay unconscious on the field. When a teammate tried to reach down and offer Williams water from a bottle, an assistant coach grabbed the bottle and angrily flung it across the field.

Throughout the drills, there was no hydration in the 83-degree heat. One player said Hunter called withholding water a form of “paying dues,” saying, “Water is for the weak.” By the time Forrest got to Williams, “he seemed to be having a seizure,” the trainer said.

On August 20, Fort Scott’s Twitter account posted: “Our Greyhound family has suffered a devastating loss. We send all our prayers, love, and support to the family of Tirrell Williams.”

The board of trustees met days later. The minutes show that in the portion of the meeting devoted to athletic department updates, they discussed the installation of artificial turf for the baseball field, the start of the volleyball season, and COVID pandemic protocols. At the end, there was a brief mention of the Williams death.

In the middle of the season, Fort Scott abruptly ended its 93-year-old football program. In 2006 the school had played in the junior college national championship game under the same head coach, Jeff Sims, who’d go on at Garden City to win one championship plus gain another championship game berth. But by November 2021, Fort Scott had fallen on hard times in the win-loss column. In a statement that month announcing the termination of the program, the college said: “We simply do not have the resources to maintain a football team that would be competitive in the Jayhawk Conference.”

President Alysia Johnston articulated her position at the next month’s trustees meeting. “We could find nothing that we did that contributed to the young man’s very unfortunate and tragic death,” she said. Johnston added that “I believe with all my heart” that Coach Hunter regarded player safety as a priority. Later, trustees chair John Bartelsmeyer would tell public radio’s Zeff, “I’m satisfied with the president and the athletic director and the administration.” As for the incident, “Specifically, I can’t say there’s anything that has been brought up to change, other than to make sure that all of our athletes are — I hate to say the word taken care of — but overseen.”

The athletic director and vice president of student affairs, Tom Havron, predicted “a great future of coaching” for Hunter. “He’s going to do great things.”

Garden City planted a tree to honor Braeden Bradforth. Fort Scott did nothing in memory of Tirrell Williams.

Carson Hunter landed a position on the football staff at the University of West Florida in Pensacola. As this book was being published, he was listed as the assistant coach for outside linebackers, and coordinator for the administration of the movements of student-athletes from school to school — newly facilitated under what NCAA procedures now call the “transfer portal.”