$125,000 Was a Small Price For Cal-Berkeley’s Already Successful Ted Agu Football Death Cover-Up. Fighting Even That Is Designed to Intimidate Anyone Daring to Use the Public Records Act to Investigate Cover-Ups.

November 8, 2022

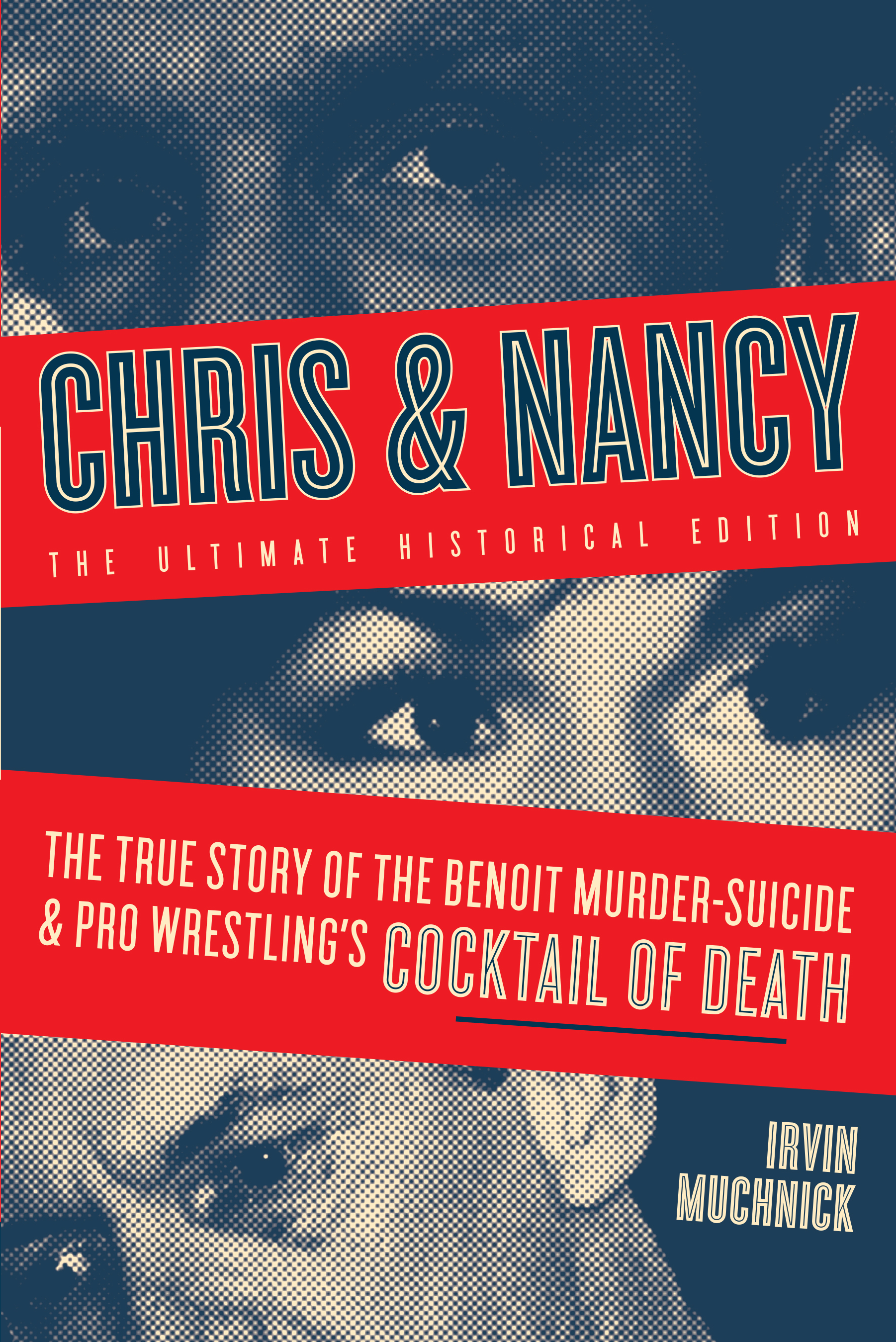

CHRIS & NANCY: The True Story of the Benoit Murder-Suicide and Pro Wrestling’s Cocktail of Death

November 10, 2022

***

PREVIOUSLY:

“In Reversal, Appellate Court Rules UC ‘Prevailing Party’ in Public Records Case – Changing Nothing About Our Daylighting of Massive New Info in Cal’s Ted Agu Football Death Cover-Up,” November 7, https://concussioninc.net/?p=15070

“$125,000 Was a Small Price For Cal-Berkeley’s Already Successful Ted Agu Football Death Cover-Up. Fighting Even That Is Designed to Intimidate Anyone Daring to Use the Public Records Act to Investigate Cover-Ups,” November 8, https://concussioninc.net/?p=15073

“In Ted Agu Football Conditioning Death Cover-Up Public Records Act Case, Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press and First Amendment Coalition Tell Appellate Court That University of California Seeks ‘to Chill Members of the Public, Including Journalists,'” March 24, https://concussioninc.net/?p=14970

“Flashback: Three Stories About the University of California’s Ted Agu Cover-Up That Were Specifically Enabled by Our Successful Public Records Act Lawsuit,” March 28, https://concussioninc.net/?p=14980

by Irvin Muchnick

A California Public Records Act petition is not supposed to be like Goodyear v. Dobbs Tire & Auto. Public information law is not constructed for someone’s commercial advantage. It is about enabling members of the public to learn more about the workings of their government and public agencies. It is about transparency and accountability.

Recognizing this, CPRA explicitly requires agencies to help make requests “focused and effective.” Implicit in this requirement is recognition that a person requesting records has no way of knowing exactly what the agency has and exactly how it is organized.

And – assuming there are issues of ambiguity when the agency fields the request – it must do the work of cooperation before the requester decides he has to go to the trouble and expense of becoming a plaintiff, or “petitioner,” in state court. Obviously, a requester-petitioner such as myself and a multibillion-dollar public entity such as the University of California have wildly asymmetrical resources. I enjoy the services of an excellent solo practitioner lawyer, Roy Gordet (who previously won a federal Freedom of Information Act case against the Department of Homeland Security for documents from the alien file of Irish Olympic swimming coach monster George Gibney). The UC Office of the President in downtown Oakland has a general counsel’s office with more than 70 lawyers.

These are among the reasons why CPRA case law has established what is called “catalyst theory.” If new and previously withheld public records are released during CPRA litigation, after the agency had made no effort to work with the requester to make the original request “focused and effective,” then the petitioner is ordinarily ruled the prevailing party. That is exactly what Alameda County Superior Court Judge Jeffrey Brand did here.

The Court of Appeal’s reversal of the lower court is disastrous. The three-judge appellate panel overrode the discretion of a judge who had presided over the case for years – often ruling against me through various motions and technical disputes, yet deciding in the end that there had been a process catalyzed by my good-faith efforts to acquire previously stonewalled material for a legitimate journalistic purpose.

In place of that, the Court of Appeal concocted a way to construe that the new documents, which emerged from court orders by Judge Brand, were outside the four corners of my original request. I strenuously disagree with such an interpretation. I have published specific articles both using these new documents and showing clearly how they pertained to my original request and its indisputable known mission all along, which was to shine light on how Cal-Berkeley officials managed the Ted Agu death and its fallout.

But even more than I disagree with contrived split hairs over whether the new documents sprang from my original request language or from the court process, I believe that CPRA is clear that the university, after doing no “focused and effective” work prior to going to court, defaulted on its ability to be named the prevailing party and to deny Gordet his fees for more than five years of advocacy for me. The only way UC should have prevailed would have been if its stone wall held and there was no new information at all, or nothing of significance, liberated by court orders.

To hold otherwise is disastrous for the incentives and equities of CPRA, and for its future functioning as a tool of civic hygiene. The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press and the First Amendment Coalition made this point well in their amicus brief, to no avail.

***

In the next and final installment of this series, I’ll address the university’s borderline, sleazy legal tactics to manipulate to a court ruling that the production of hundreds of pages of previously withheld pages was “their” work rather than “mine.” Those tactics crossed all the way over into blatant lies in court filings by the UC general counsel’s office.